World War II Events

Local Events in World War II

Unfamiliar sights and sounds were disturbing their normal tranquil lives. Barrage balloons, moored on Harwich Green, hung ponderously over the town and the taut wires sang and sighed in the breezes to keep them awake at night. Long fingers of searchlights beat out the stars as they felt there was across clear skies and their trigonometrical patterns were mirrored in the calm seas of that glorious summer.

The harbour became once more an important but vulnerable base with its minesweepers, submarines and destroyers. The menace of Mines caused Harwich many alerts-the enemy frequently came in close to drop these deadly weapons.

Harwich, like all other towns, rejoiced in the turning of the tide and residents had a grandstand view of our planes roaring over to pound the enemy.

The borough if Harwich had 1,200 air raid alerts and no less than 1,750 Bombs were dropped.

Simon Bolivar

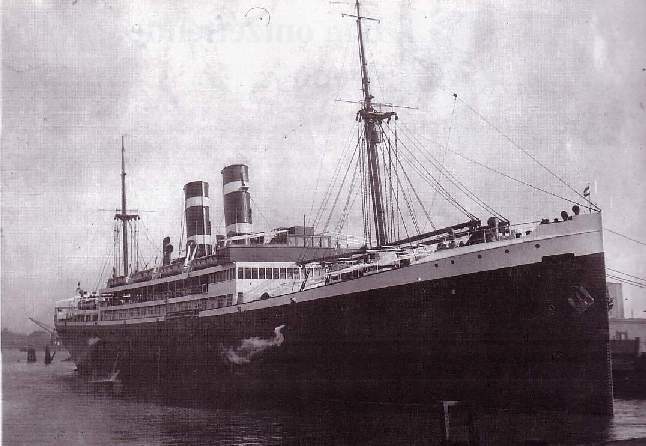

Built in 1927 the Dutch passenger ship of 8,309 tons could carry 238 passengers in three classes and sailed the Hamburg-Central America route.

Simon Bolivar

Owned by the Royal Netherlands Steamship Company, she was en route to the West Indies from Amsterdam when she struck a magnetic mine at 12.30 pm on the 18th November 1939 about twenty-five miles from Harwich. Captain Voorspuity and 83 passengers lost their lives. Passing ships picked up survivors and took them either to Harwich or London.

Simon Bolivar

People were playing games on deck when a terrific explosion hit the Simon Bolivar under the bridge. Captain Voorspuity was killed instantly. The liner’s oil pipes burst and the ship listed heavily, making it difficult to lower the boats. Many passengers swarmed down the ropes or jumped over the side.

A Sister of Charity nun was rescued clinging to a piece of driftwood. One British passenger, Sydney Preece of Maidenhead, put his three year old daughter in a wooden box and swam with it through the oil-covered icy water for nearly an hour.

The Simon Bolivar then plunged to the bottom but so shallow was the water where she sunk that the tops of the masts and funnels remained above water. On shore a clearing station was established and local railway ambulances were called upon as well as all available first aiders from the a.r.p services in readiness for the arrival of the survivors as ambulances whisked the injured as they were landed to the Harwich and District Hospital.

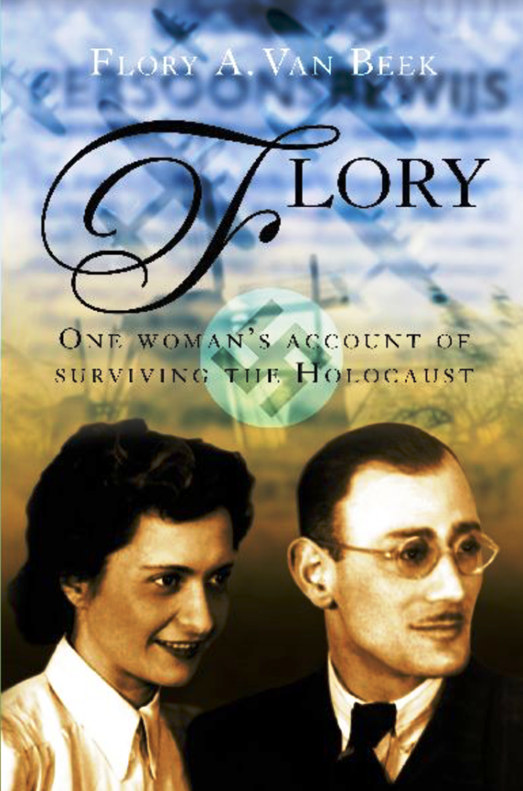

A Miraculous Story of Survival

In 1939, as the Nazi occupation grew from threat to reality, the Jewish population throughout Europe faced heart-wrenching decisions—to flee and lose their homes or to go into hiding, hoping against all odds to avoid the fate of being discovered. Holocaust survivor Flory A. Van Beek faced this terrible choice, and in this poignant testament of hope she takes us on her personal journey into one of history’s darkest hours.

Flory: A Miraculous Story of Survival

Only a teenage girl when the Nazis invaded her neutral homeland of Holland, Flory watched the only life she had ever known disappear. Tearfully leaving her family, Flory tried to escape on the infamous SS Simon Bolivar passenger ship with Felix, the young Jewish man from Germany who would later become her husband. Their voyage brought not safety but more peril as their ship was blown up by Nazi planted mines, one of the first passenger ships destroyed by the Germans during World War II, sending nearly all of its passengers to a watery end. Miraculously, both Flory and Felix survived.

Flory & Felix were repatriated back to Holland in May 1940 just before the arrival of the Germans, Unfortunately their Jewish ancestry was discovered and they were forced to wear “The Star of David”.

As the Nazi grip tightened, they were forced into hiding. Sheltered by compassionate strangers in confined quarters, cut off from the outside world and their relatives, they faced hunger and the stress of daily life shadowed by the ever-present threat of certain death. Yet they also discovered, with the remarkable and brave families who sacrificed their own safety to help keep Flory and Felix alive, a set of friends that remain as close as family to this day.

Flory emigrated to America in 1948 carrying a suitcase full of papers and photographs that she had buried while in hiding during the German occupation. The material now forms one of the largest collections from the Netherlands housed in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum of Washington, DC.

Flory Van Beek

Dutch public opinion is outraged because the mine was in a major traffic lane. International law as well as common humanity, requires that any such mine-laying must be notified. The Dutch believe that the mines are a deadly new magnetic type. This view was supported today by a Danish skipper, Captain Knudsen, giving evidence in Copenhagen about the sinking of his ship, ‘Canada’, off the Humber on 4 November. The Germans, who claim that their U-boats sank 115 ships in the first two months of the war, are clearly putting a further massive effort into the war at sea. The total British tonnage lost so far is small, only around 300,000 out of nearly 18 million tons. No one knows how many mines are already laid.

Terukuni Maru

The Terukuni Maru Was a Japanese Ocean Liner owned by Nippon Yusen Kaisha (NYK). Launched in 1929 By Mitsubishi Shipbuilidng & Engineering Co. at Nagasaki, Japan, she entered service in 1930.

The 11,931-ton steel-hulled vessel had a length of 505 feet (154 m), and a beam of 64 feet (20 m), with a single funnel, two masts, and double screws. Terukuni Maru provided accommodation for 121 first-class passengers and 68 second class passengers. There was also room for up to 60 third-class passengers. The ship and passengers were served by a crew of 177.

Final Voyage

On September 24, 1939, at 5 pm. The Japanese ocean Liner departed Yokohama on her 25th voyage to Europe. En route, she made her usualscheduled ports of call: Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Moji, Shanghai , Hong Kong , Singapore , Penang , and Colombo . After transiting the Suez Canal, she called at Beirut ,Naples and Marseille., she transited the Dver Straits , turning north to the mouth of the Thames River and her final destination of London . She took aboard a pilot off the South Downs, and underwent contraband inspection while Royal Navy minesweepers checked her route into London for mines. After receiving clearance to proceed, at 35 minutes after midnight on the morning of November 21, an explosion occurred between her second and third holds, after she struck a German magnetic mine Off Harwich . She sank in less than 45 minutes, but there were no fatalities as all 28 passengers and 177 crew members were able to escape in lifeboats.

As Japan was officially neutral at the time, the sinking of the Terukuni Maru led to a diplomatic incident between Japan and both the United Kingdom and Germany. Both countries officially denied responsibility for the mine. However, it is almost certain to have been a German mine because the type of mine used is one that had been developed by the Germans and because the United Kingdom would not have placed mines in its own shipping lanes. Although Japan was increasingly allied towards Germany, the Japanese government protested the loss with the Nazi German government, but the ship owner was not compensated for the loss.

The wrecked ship rested on its side at 8 fathoms (48 ft.; 15 m) depth. The wreckage was examined for salvage potential, but salvage work was not undertaken. In 1946 the ship was demolished with explosives as part of a British effort to remove war debris from coastal waters.

Her sinking has been described as Japan’s only World War II casualty outside of East Asia before the 1941attack on Pearl Harbor.

H.M.S Gypsy

H.M.S. Gipsy

At 1620 on Tuesday 21st November 1939 Rear Admiral Charles Harris, Flag Officer in command HMS Badger the naval base at Harwich received an Admiralty signal telling him to send four of his destroyers out that evening into the North Sea to counter U-boats coming across to mine the Thames estuary. HMS Gipsy had only returned at 1830, landing the three crew members of the downed German seaplane and were ordered to return to sea in an hour. At 1930 two seaplanes were spotted coming in low at, about 150 feet, from Landguard Fort a gun emplacement protecting the approaches to Harwich. At this time in November it was pitch black so searchlights were switched on and the planes picked out. As they looped over the Harwich harbour boom each seaplane was seen to drop at least one object into the harbour mouth. A parachute was spotted and bearings taken of where the objects had fallen.

Heinkel 59e

The planes, which were Heinkel HE59s, below, remained unidentified and not a single shot was fired at them by Anti-Aircraft guns. The seaplanes, of an obsolete design, with a top speed of 137mph, open cockpits and banking at a low altitude right beside the fort and “coned” by searchlights should have made a viable target for the Lewis gunners of the Coast Artillery Regiment.

AA command’s standing orders stated that only aircraft that had been positively identified could be fired upon in a measure to protect the RAF from “friendly fire”. There was also a RAF seaplane base at nearby Felixstowe which may have stayed the gunner’s hands. It was also generally not known that the Germans dropped mines by parachutes which may have led to a belief that this was aircrew bailing out. The AA gunners at Landguard fort must of seen the German insignia and swastikas but still thought they were prohibited from firing without orders. These did eventually come but the planes had long gone by then. These mistakes were the first in a chain of failings that led to the tragic loss HMS Gipsy.

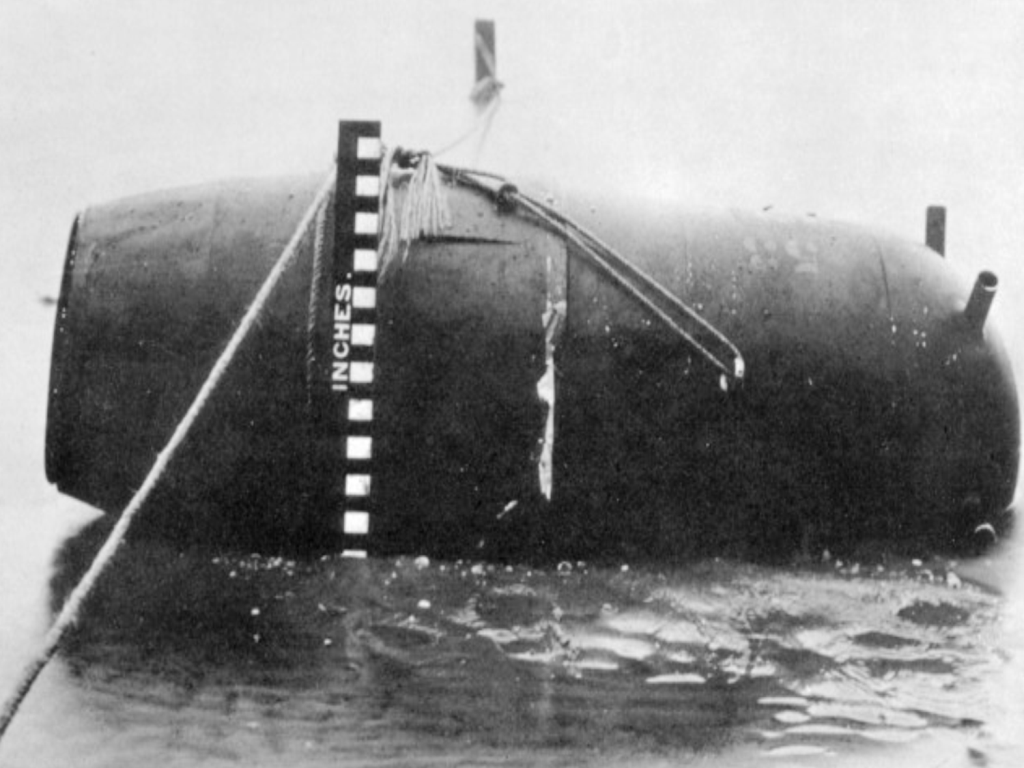

Type GA Magnetic mine

Officers at Landguard fort phoned Rear Admiral Harris at 1936 and told him about the seaplanes and the suspected mines. Harris ordered the harbour entrance closed and a search for the mines was carried out by gunners from the fort and a launch from RAF Felixstowe. This however was hampered by the high tide and darkness. Harris had planned to send his destroyers out at 2000, in only 20 minutes time. A better search could be carried out in daylight and at low tide. Harris phoned his superior officer, Admiral Brownrigg at Chatham but was told that it was imperative that the destroyers should set sail as soon as possible and that any delays were kept to a minimum. Harris decided to keep his destroyers at their moorings for the moment, and informed the flotilla Commander, Captain Creasy of the situation. After half an hours searching no trace of any mine had been found. It would not be possible to carry out a proper search for many hours and as the mines were almost certainly magnetic could not be cleared by conventional means. With his superior officer’s insistence that the mission was urgent, Harris ordered each destroyer to be signalled by aldis lamp (there was no RT on British warships in 1939). The signal revised the time of departure to 2050 and stated:

“Proceed in execution of previous orders. When passing the entrance keep as far to the starboard side of the channel as possible, leaving cliff foot buoy close on port”

At 2046 Captain Creasey cast “Griffin” off and ordered an Aldis lamp signalled to all ships to follow from their various moorings. In the last hour Creasey had not told the rest of his flotilla about the mines although he knew of their existence and approximate location. His Captains therefore did not take any extra precautions such as move as many sailors as possible away from vulnerable lower decks and port side of the ship. The ships left in the order of their identification numbers. The Polish “Burza” first followed by “Griffin”, “Gipsy”, “Keith”, “Bodicea” and finally another Pole “Grom”. Moving out at about 10 knots the first two ships steered far to the starboard. “Gipsy”, third in line was following in “Griffin’s” wake, not having set a compass course for the west side of the channel. The strong ebbing tide pulled the ship back into the centre of the channel. They were just correcting the course when a 2123, still short of the Cliff Foot buoy there was an ear-splitting crash and “Gipsy” was jolted, lifted out of the water and broke in half. She had blown the most northerly of the two mines, which was some 250 yards further west of the estimated position. The ship drifted two hundred yards then slewed round in the channel.

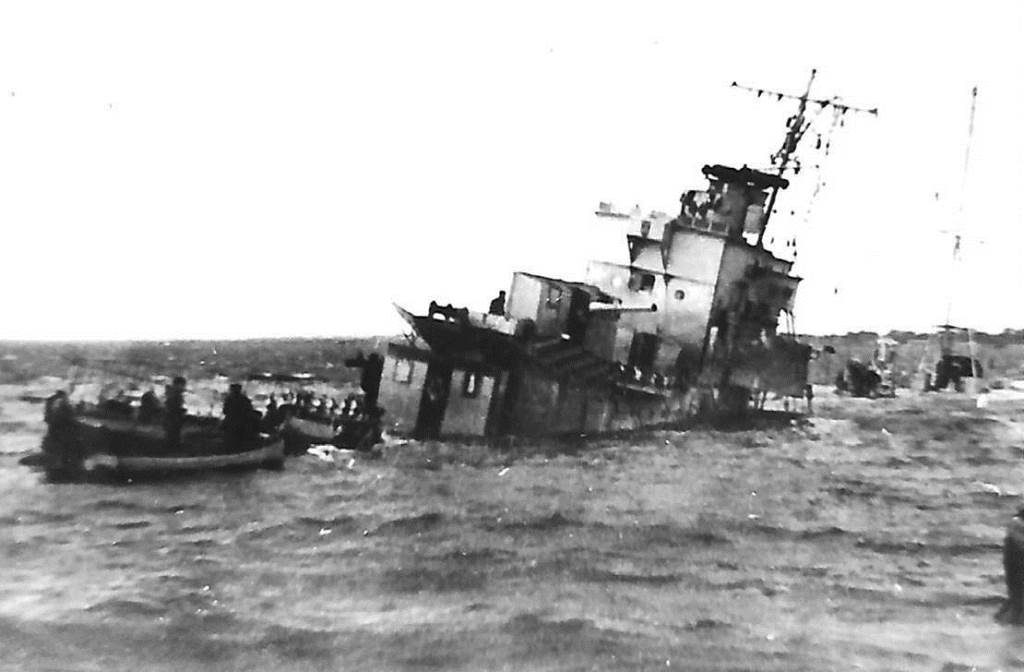

H.M.S Gypsy

The jolt had thrown Lt-Cdr Crossley off his open bridge onto the forecastle shattering his skull. The ship had broken exactly amidships between the two funnels. The boiler and engine rooms were flooded and many of their occupants drowned. The explosion had been heard on both sides of the estuary and many civilians and servicemen rushed to the waterside. The searchlights at Landguard fort were turned on sweeping across the dark water as launches from the now halted destroyers and from shore bases sped to the rescue. Many men had either fell or jumped into the water and these along with other survivors, including Crossley were picked up. The injured were transported to HMS Ganges the RN training establishment at nearby Shotley.

Thirty sailors had died, 29 bodies still trapped in the wreckage.

Lt Cdr. Nigel Crossley

Nigel Crossley was seriously injured and also lost was his pet bull terrier Benjamin who always sailed with him and was by his side when Gipsy was mined. The remaining destroyers broke off from the rescue at 2300 and went across on the anti-U boat sweep. This proved fruitless as there were no German warships of any kind in the southern North Sea that night. Lt-Cdr Crossley along with other injured sailors was being treated in the sickbay of HMS Ganges. He was still in a coma and despite head surgery he died on Monday 27th November. He was 35.

Shotley Church

He was buried two days later in the naval cemetery next to Shotley Church up the hill from HMS Ganges and overlooking the Harbour. His flag draped coffin was pulled by boy sailors from the Ganges. It was a dank gloomy day and his widow Marjorie was waiting. A party of ratings from HMS Badger fired a volley of shots as his coffin was lowered into the grave.

Churchill’s anger over the incident led to Admiral Brownrigg being demoted for his inflexibility and the officer commanding coastal artillery for his negligence.

An enquiry into the sinking of the Gipsy was opened on the 13th December at a hotel in Harwich questioning officers from the Gipsy as well as the other destroyers as well as Harris and other shore based officers.

The enquiry took two days and its witnesses asked 157 questions. The enquiry attached no blame to anyone, the only implied criticism coming in the recommendation “all units should have full information of the danger to be avoided”

Wreck of H.M.S. Gypsy

On the 24th November 1939 the Chief Constructor of the Navy inspected the wreck.

The next day temporary anchors were put in place to stop it shifting or disintegrating further. Sailors removed the foremast, guns, torpedo tubes and depth charges. At low tide on the 28th December local tugs secured the two halves of the wreck to giant floats so as when the tide rose the wreck cleared the bottom. The two halves were then towed up the channel and beached off RAF Felixstowe.

There was some consideration given to re-joining the two halves but this was soon ruled out. In August 1940 the stern half was towed across the harbour and beached on Harwich Hard where it was broken up over the next few years. The bow section being close to the shipping channel was blown up in 1942.

A report in the press at the time stated

“Gipsy had never killed any Germans only saved some”

Relating to the three German airman she had rescued before sailing to her doom.

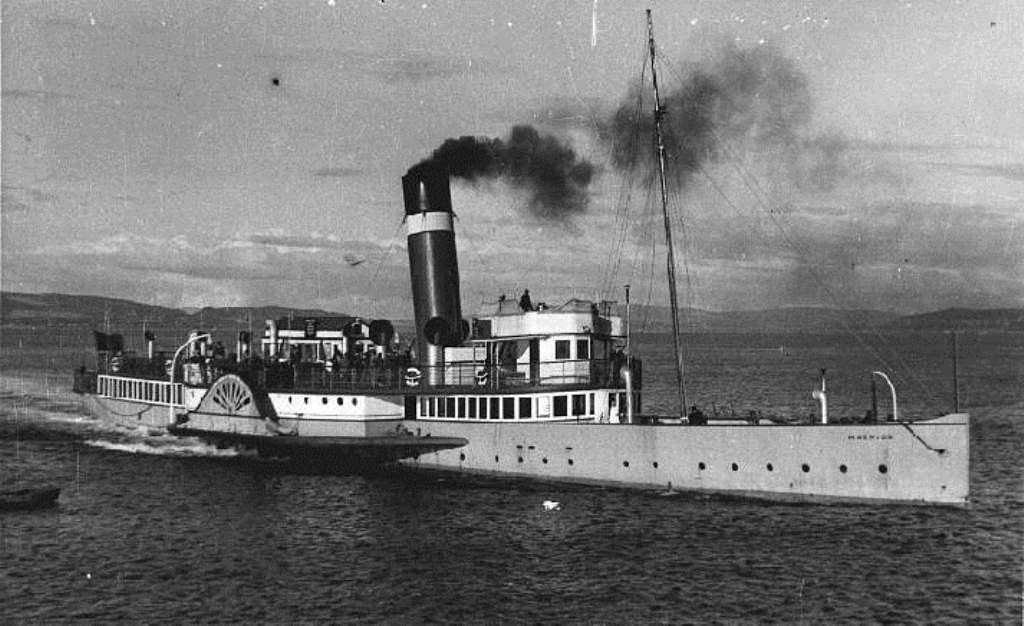

H.M.S Marmion

H.M.S. Marmion

Launched on May 5 1906 at A. & J.Inglis at Pointhouse, Glasgow, the 403 ton Marmion was used on the Arrochar and Loch Goil service for the North British Steam Packet Company. She was requisitioned for minesweeping at Dover from 1915 as HMS Marmion II, and returned to regular Clyde service in 1926. Again she was requisitioned for war service, stationed at Harwich. After surviving the Dunkirk evacuation, she was sunk by enemy bombers at Harwich on the night of April 9 1941 and was later raised and scrapped.

H.M.S Marmion

A Single bomb Sank “Marmion, 9 Killed, 22 Wounded.

It took 6 weeks to refloated before being towed away to Pin Mill to be broken up.

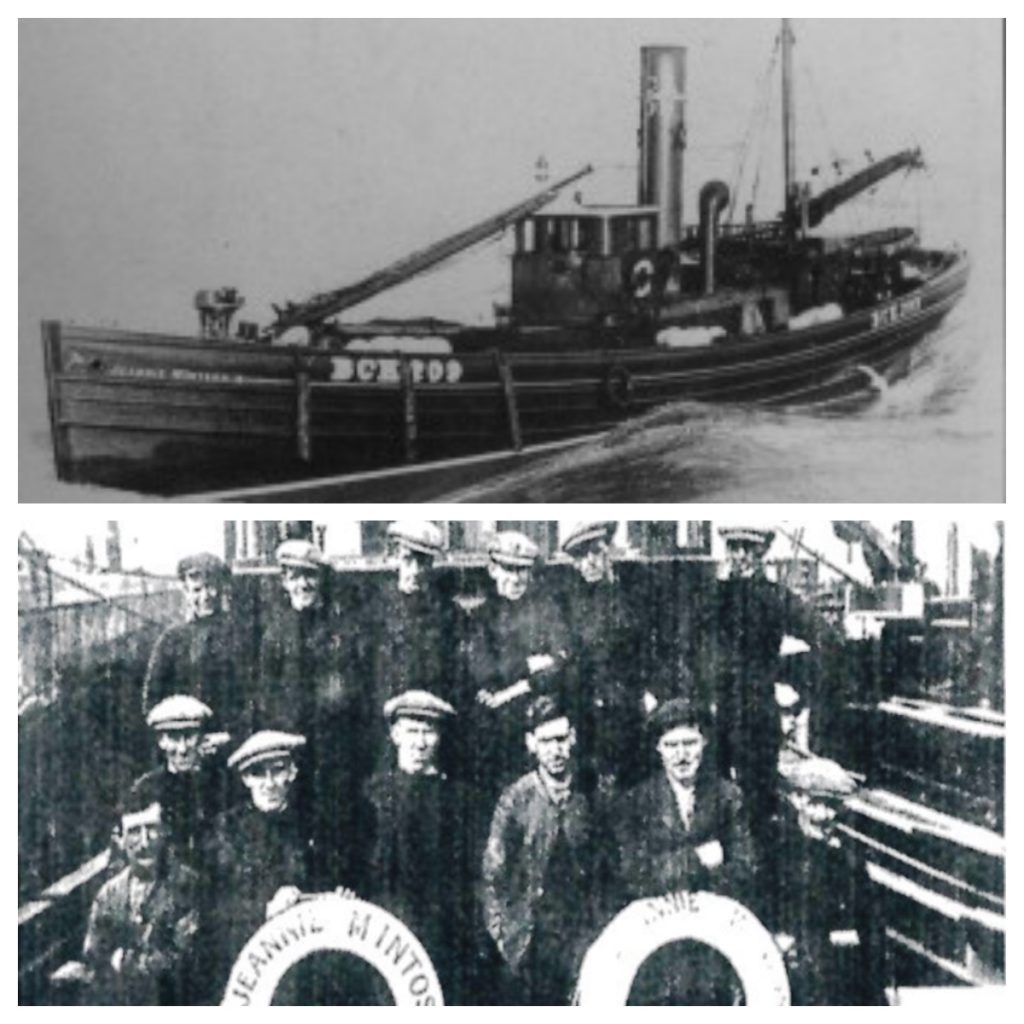

Jeanie McIntosh

Jeannie McIntosh

Launched by shipbuilder William Robertson McIntosh in February 1915 for himself. It is believed he named her after his eldest daughter Jane – who was known as Jeannie. Requisitioned by the Admiralty in 1915 and used throughout The Great War as a boom defence vessel/ water carrier. Returned to W. R. McIntosh in 1919.

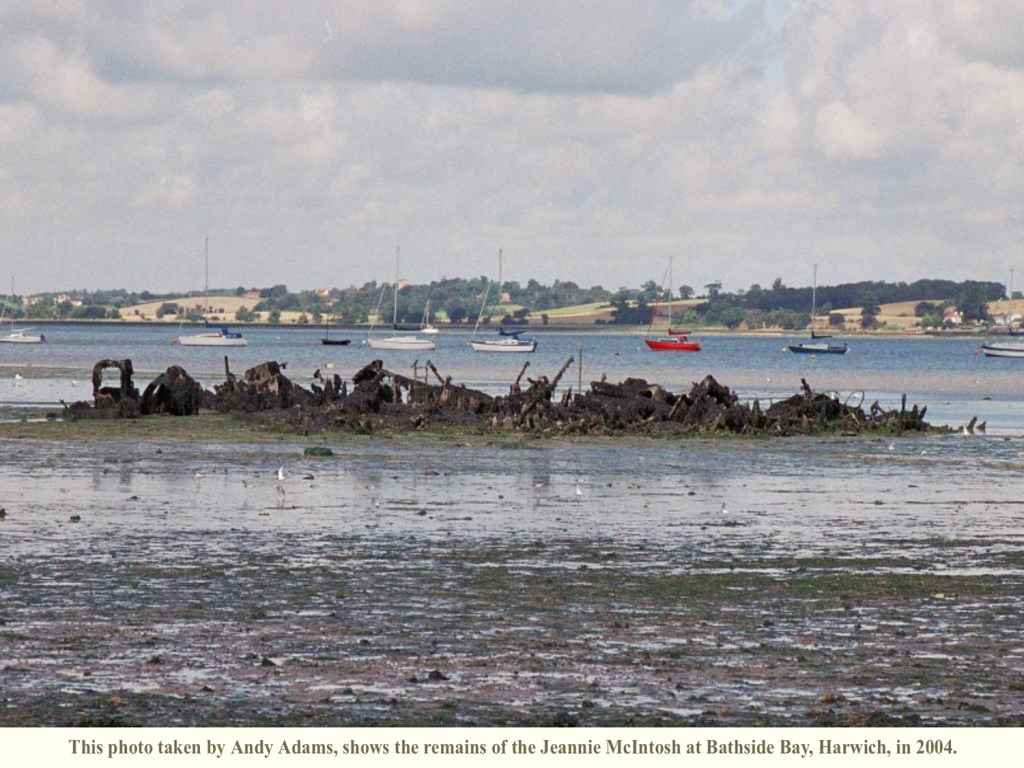

One of a flotilla of 13 drifters attached to Yarmouth Base (H.M.S. Watchful). This flotilla participated in the evacuation at Dunkirk in 1940. Jeannie McIntosh was among those who sustained damage but made it back to Harwich under her own power. She was seemingly repaired & assigned to a patrol escort group based at Ipswich. Armed with machine guns she was probably engaged in escorting small ship convoys, to and from Ipswich and Harwich, to join the main East Coast convoy route about 11 miles off Harwich. When the Rough Fort was placed in position in February 1942 about seven miles off Harwich, Essex, she was then allocated as a tender and subsequently the Sunk Head Fort – finally being scrapped in 1947. She was abandoned in Bathside Bay, Harwich and her remains can still be seen at low tide.

Jeannie Mcintosh

She was one of the biggest wooden drifters built with a 40 foot steam engine, She became a playground for the boys of the Bathside. We used to walk out to her and swim back on the high tide.

It was painted grey except for a lovely painting on the wheel house showing all the faces of the crew pulling in herring nets when she was a herring drifter. She still had all the pots and pans in the galley and all the goodies were left on her.

Then the Harwich fishermen took the steam coal off for their shrimp boilers and everything else that moved.

She was sold to a Harwich scrap metal merchant, who removed all the steel off her which fetched a good price after the war.

She started to break up in 1953 and ion the Harwich flood, a big part of the Jeannie McIntosh hit the house at the top of Maria Street and Stour Road. D. Lovett

V2 rocket in Harwich Harbour

A German V2 rocket from World War II was found nose down in the mud flats at Harwich Harbour in March 2012.

V2 rocket

At low tide, it was about 200m (656ft) from the shore near Harwich Yacht Club.

The V2, which was used by the Germans from 1944, was 46ft (14m) long.

It was placed on a barge for transfer to dry land during the afternoon high tide on Saturday.

A witness remembered a V2 rocket, which was 46ft (14m) long, exploding over the port in 1944.

It is an unusual find as the V2 rockets were usually obliterated due to the speed with which they plunged to earth, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) said.

Astonishingly sailors and fishermen had been mooring their boats to the wreckage for years without realising what it was.

The only witness to the V-2 landing in Harwich was 16-year-old fisherman Reuben Day who described the sound as like a tube train going through the air.

Reuben spent his adult life claiming a rocket had landed in the estuary after seeing it hit the water – but no-one believed him.

He reported seeing a vapour trail of black and white smoke and went to investigate with a policeman.

Experts believe it was launched without an explosive warhead because the impact alone would have been great enough to cause devastation.

Just over 1,400 V-2s fell on England in 1944 and 1945, killing an estimated 2,754 civilians in London and injuring more than 6,500.

A delicate retrieval operation was carried out and the rocket has been stored by Harwich Town Sailing Club.

V2 rocket

Now it has pride of place at the Redoubt Fort where it will be on permanent display.

Colin Farnell, Harwich Society chairman, said: “The Redoubt was built to deal with Napoleonic munitions and it was a tense time as this more modern weapon completed its journey.

I believe it is important for the people of Harwich to be able to come and see one of these monsters that could so easily have destroyed a large part of our historic town and claimed countless local lives.

Photo Gallery

We are adding more information to this site on a regular basis, if you wish to submit any photos or provide any information, please use the contact page at the bottom of the screen.

Acknowledgements:

- The Harwich Society, Julian Foynes.