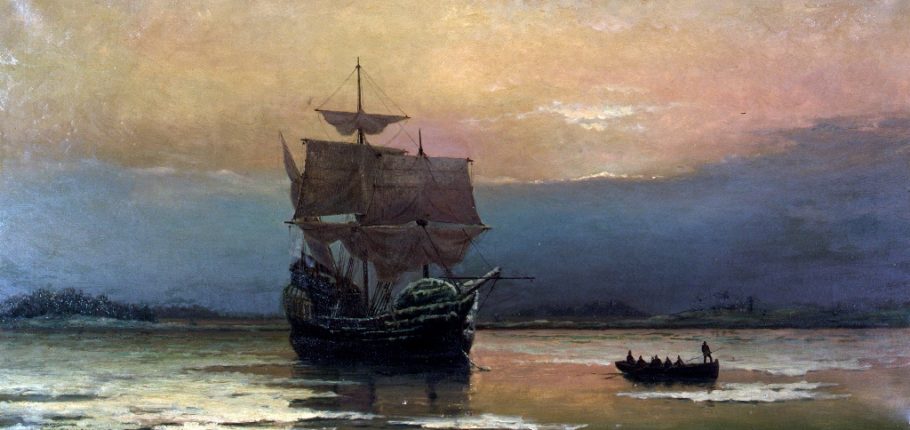

The Mayflower

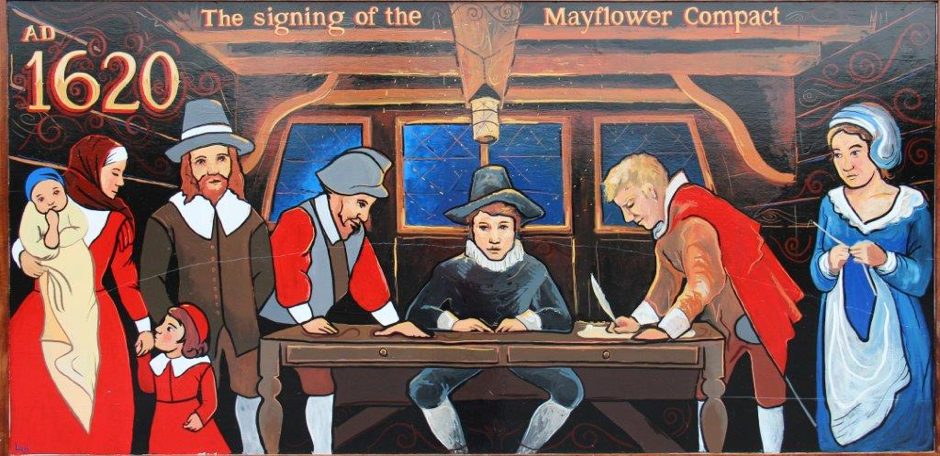

The Mayflower was an English ship that transported the first English Puritans, known today as the Pilgrims, from Plymouth, England, to the New World in 1620. There were 102 passengers, and the crew is estimated to have been about 30, but the exact number is unknown. The Pilgrims signed the Mayflower Compact prior to leaving the ship and establishing Plymouth Colony, a document which established a rudimentary form of democracy with each member contributing to the welfare of the community.

Mayflower

The Mayflower was a square rig with a beakhead bow and high, castle-like structures fore and aft that served to protect the ship’s crew and the main deck from the elements—designs that were typical with English merchant ships of the early 17th century. Her stern carried a 30-foot high, square aft-castle which made the ship extremely difficult to sail against the wind and unable to sail well against the North Atlantic’s prevailing westerlies, especially in the fall and winter of 1620; the voyage from England to America took more than two months as a result. The Mayflower‘s return trip to London in April–May 1621 took less than half that time, with the same strong winds now blowing in the direction of the voyage.

The exact dimensions are not known for the Mayflower, but she probably measured about 100 feet (30 m) in length from the beak of her prow to the tip of her stern superstructure, about 25 feet (7.6 m) at her widest point, and the bottom of her keel about 12 feet (3.6 m) below the waterline. William Bradford estimated that she had a cargo capacity of 180 tons, and surviving records indicate that she could carry 180 casks holding hundreds of gallons each.

Aft on the main deck in the stern was the cabin for Master Christopher Jones, measuring about ten by seven feet (3 m × 2.1 m). Forward of that was the steerage room, which probably housed berths for the ship’s officers and contained the ship’s compass and whipstaff (tiller extension) for sailing control. Forward of the steerage room was the capstan, a vertical axle used to pull in ropes or cables. Far forward on the main deck, just aft of the bow, was the forecastle space, where the ship’s cook prepared meals for the crew; it may also have been where the ship’s sailors slept.

The poop deck was located on the ship’s highest level above the stern on the aft castle and above Master Jones’ cabin. On this deck stood the poop house, which was ordinarily a chart room or a cabin for the master’s mates on most merchant ships; but on the Mayflower, it might have been used by the passengers, either for sleeping or cargo.

The gun deck was where the passengers resided during the voyage, in a space measuring about 50 by 25 feet (15.2 m × 7.6 m) with a five-foot (1.5 m) ceiling. But it was a dangerous place if there was conflict, as it had gun ports from which cannon could be run out to fire on the enemy. The gun room was in the stern area of the deck, to which passengers had no access because it was the storage space for powder and ammunition. The gun room might also house a pair of stern chasers, small cannon used to fire from the ship’s stern. Forward on the gun deck in the bow area was a windlass, similar in function to the steerage capstan, which was used to raise and lower the ship’s main anchor. There were no stairs for the passengers on the gun deck to go up through the gratings to the main deck, which they could reach only by climbing a wooden or rope ladder.

Below the gun deck was the cargo hold where the passengers kept most of their food stores and other supplies, including most of their clothing and bedding. It stored the passengers’ personal weapons and military equipment, such as armor, muskets, gunpowder and shot, swords, and bandoliers. It also stored all the tools that the Pilgrims would need, as well as all the equipment and utensils needed to prepare meals in the New World. Some Pilgrims loaded trade goods on board, including Isaac Allerton, William Mullins, and possibly others; these also most likely were stored in the cargo hold. There was no privy on the Mayflower; passengers and crew had to fend for themselves in that regard. Gun deck passengers most likely used a bucket as a chamber pot, fixed to the deck or bulkhead to keep it from being jostled at sea.

The Mayflower was heavily armed; her largest gun was a minion cannon which was brass, weighed about 1,200 pounds (545 kg), and could shoot a 3.5 pound (1.6 kg) cannonball almost a mile (1,600 m). She also had a saker cannon of about 800 pounds (360 kg), and two base cannons that weighed about 200 pounds (90 kg) and shot a 3 to 5 ounce ball (85–140 g). She carried at least ten pieces of ordnance on the port and starboard sides of her gun deck: seven cannons for long range purposes, and three smaller guns often fired from the stern at close quarters that were filled with musket balls. Ship’s Master Jones unloaded four of the pieces to help fortify Plymouth Colony against invaders.

Approximately 65 passengers embarked the Mayflower in the middle of July 1620 at either Blackwall or Wapping on the River Thames. The ship then proceeded down the Thames into the English Channel and then on to the south coast of England to anchor at Southampton Water. She waited there for a rendezvous on July 22 with the Speedwell, which was coming from Holland with English separatist Puritans, members of the Leiden congregation who had been living in Holland to escape religious persecution in England.

Both ships set sail for America around August 5, but the Speedwell sprang a leak shortly after, and the two ships were brought into Dartmouth for repairs. They made a new start after the repairs, and they were more than 200 miles (320 km) beyond Land’s End at the southwestern tip of England when Speedwell sprang another leak. It was now early September, and they had no choice but to abandon the Speedwell and make a determination on her passengers. This was a dire event, as the ship had wasted vital funds and was considered very important to the future success of their settlement in America. Both ships returned to Plymouth, where some of the Speedwell passengers joined the Mayflower and others returned to Holland. The Mayflower then continued on her voyage to America, and the Speedwell was sold soon afterwards.

Mayflower carried 102 passengers plus a crew of 25 to 30 officers and men, bringing the total to approximately 130. According to William Bradford, Speedwell was refitted and “made many voyages… to the great profit of her owners.” He also suggested that the Speedwell’s master used “cunning and deceit” to abort the voyage, possibly by causing leaks in the ship and motivated by a fear of starving to death in America.

Mayflower sets sail

In early September, western gales began to make the North Atlantic a dangerous place for sailing. The Mayflower’s provisions were already quite low when departing Southampton, and they became lower still by delays of more than a month. The passengers had been on board the ship for this entire time, and they were worn out and in no condition for a very taxing, lengthy Atlantic journey cooped up in the cramped spaces of a small ship. But the Mayflower sailed from Plymouth on September 6, 1620 with what Bradford called “a prosperous wind”.

Aboard the Mayflower were many stores that supplied the pilgrims with the essentials needed for their journey and future lives. It is assumed that they carried tools and weapons, including cannon, shot, and gunpowder, as well as some live animals, including dogs, sheep, goats, and poultry. Horses and cattle came later. The ship also carried two boats: a long boat and a “shallop”, a 21-foot boat powered by oars or sails. She also carried 12 artillery pieces, as the Pilgrims feared that they might need to defend themselves against enemy European forces, as well as the Indians.

The passage was a miserable one, with huge waves constantly crashing against the ship’s topside deck, fracturing a key structural support timber. The passengers had already suffered agonizing delays, shortages of food, and other shortages, and they were now called upon to provide assistance to the ship’s carpenter in repairing the fractured main support beam. This was repaired with the use of a metal mechanical device called a jackscrew, which had been loaded on board to help in the construction of settler homes. It was now used to secure the beam to keep it from cracking farther, thus maintaining the seaworthiness of the vessel.

The crew of the Mayflower had some devices to assist them en route, such as a compass for navigation, as well as a log and line system to measure speed in nautical miles per hour (knots). Time was measured with the ancient method of an hourglass.

Arrival in America

On November 9, 1620, they sighted present-day Cape Cod. They spent several days trying to sail south to their planned destination of the Colony of Virginia, where they had obtained permission to settle from the Company of Merchant Adventurers. However, strong winter seas forced them to return to the harbour at Cape Cod hook, well north of the intended area, where they anchored on November 11. The settlers wrote and signed the Mayflower Compact after the ship dropped anchor at Cape Cod, in what is now Provincetown Harbor, in order to establish legal order and to quell increasing strife within the ranks.

On Monday, November 27, an exploring expedition was launched under the direction of Capt. Christopher Jones to search for a suitable settlement site. As master of the Mayflower, Jones was not required to assist in the search, but he apparently thought it in his best interest to assist the search expedition. There were 34 persons in the open shallop: 24 passengers and 10 sailors. They were obviously not prepared for the bitter winter weather which they encountered on their reconnoitre, the Mayflower passengers not being accustomed to winter weather much colder than back home. They were forced to spend the night ashore due to the bad weather which they encountered, ill-clad in below-freezing temperatures with wet shoes and stockings that became frozen. Bradford wrote, “Some of our people that are dead took the original of their death here” on that expedition.

The settlers explored the snow-covered area and discovered an empty native village, now known as Corn Hill in Truro. The curious settlers dug up some artificially made mounds, some of which stored corn, while others were burial sites. The modern writer Nathaniel Philbrick claims that the settlers stole the corn and looted and desecrated the graves, sparking friction with the locals. Philbrick goes on to say that they explored the area of Cape Cod for several weeks as they moved down the coast to what is now Eastham, and he claims that the Pilgrims were looting and stealing native stores as they went. He then writes about how they decided to relocate to Plymouth after a difficult encounter with the Nausets at First Encounter Beach in December 1620.

However, the only contemporary account of events, William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, records only that the pilgrims took “some” of the corn, to show to others back at the boat, leaving the rest. They later took what they needed from another store of grain,

Also there was found more of their corn and of their beans of various colours; the corn and beans they brought away, purposing to give them full satisfaction when they should meet with any of them as, about some six months afterward they did, to their good content.

but paid the natives back in six months, and there was no resulting conflict.

First winter

During the winter, the passengers remained on board the Mayflower, suffering an outbreak of a contagious disease described as a mixture of scurvy, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. When it ended, only 53 passengers remained—just over half; half of the crew died, as well. In the spring, they built huts ashore, and the passengers disembarked from the Mayflower on March 21, 1621.

The settlers decided to mount “our great ordnances” on the hill overlooking the settlement in late February 1621, due to the fear of attack by the natives. Christopher Jones supervised the transportation of the “great guns”—about six iron cannons that ranged between four and eight feet (1.2 to 2.4 m) in length and weighed almost half a ton. The cannons were able to hurl iron balls 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) in diameter as far as 1,700 yards (1.5 km). This action made what was no more than a ramshackle village almost into a well-defended fortress.

Jones had originally planned to return to England as soon as the Pilgrims found a settlement site. But his crew members began to be ravaged by the same diseases that were felling the Pilgrims, and he realized that he had to remain in Plymouth Harbor “till he saw his men began to recover.” The Mayflower lay in New Plymouth harbour through the winter of 1620–21, then set sail for England on April 5, 1621, her empty hold ballasted with stones from the Plymouth Harbor shore. As with the Pilgrims, her sailors had been decimated by disease. Jones had lost his boatswain, his gunner, three quartermasters, the cook, and more than a dozen sailors.

The Mayflower made excellent time on her voyage back to England. The westerly winds that had buffeted her coming out pushed her along going home, and she arrived at the home port of Rotherhithe in London on May 6, 1621, less than half the time that it had taken her to sail to America.”

Jones died after coming back from a voyage to France on March 5, 1622, at about age 52. For the next two years, the Mayflower lay at her berth in Rotherhithe, not far from Jones’ grave at St. Mary’s church. By 1624, she was no longer useful as a ship; her subsequent fate is unknown, but she was probably broken up about that time.

Passengers

Some families traveled together, while some men came alone, leaving families in England and Leiden. Two wives on board were pregnant; Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth to son Oceanus while at sea, and Susanna White gave birth to son Peregrine in late November while the ship was anchored in Cape Cod Harbor. He is historically recognized as the first European child born in the New England area. One child died during the voyage, and there was one stillbirth during the construction of the colony.

According to the Mayflower passenger list, just over a third of the passengers were Puritan Separatists who sought to break away from the established Church of England and create a society along the lines of their religious ideals. Others were hired hands, servants, or farmers recruited by London merchants, all originally destined for the Colony of Virginia. Four of this latter group of passengers were small children given into the care of Mayflower pilgrims as indentured servants. The Virginia Company began the transportation of children in 1618. Until relatively recently, the children were thought to be orphans, foundlings, or involuntary child labor. At that time, children were routinely rounded up from the streets of London or taken from poor families receiving church relief to be used as laborers in the colonies. Any legal objections to the involuntary transportation of the children were overridden by the Privy Council. For instance it was proven that the four More children were sent to America because they were deemed illegitimate. Three of the four More children died in the first winter in the New World, but Richard lived to be approximately 81, dying in Salem, probably in 1The passengers mostly slept and lived in the low-ceilinged great cabins and on the main deck, which was 75 by 20 feet large (23 m × 6 m) at most. The cabins were thin-walled and extremely cramped, and the total area was 25 ft by 15 ft (7.6 m × 4.5 m) at its largest. Below decks, any person over five feet (150 cm) tall would be unable to stand up straight. The maximum possible space for each person would have been slightly less than the size of a standard single bed.

Passengers would pass the time by reading by candlelight or playing cards and games such as Nine Men’s Morris. Meals on board were cooked by the firebox, which was an iron tray with sand in it on which a fire was built. This was risky because it was kept in the waist of the ship. Passengers made their own meals from rations that were issued daily and food was cooked for a group at a time.

Upon arrival in America, the harsh climate and scarcity of fresh food were exacerbated by the shortness of provisions due to the delay in departure. Living in these extremely close and crowded quarters, several passengers developed scurvy, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. At the time the use of lemons or limes to counter this disease was unknown, and the usual dietary sources of vitamin C in fruits and vegetables had been depleted, since these fresh foods could not be stored for long periods without their becoming rotten. Passengers who developed scurvy experienced symptoms such as bleeding gums, teeth falling out, and stinking breath.

Passengers consumed large amounts of alcohol such as beer with meals. This was known to be safer than water, which often came from polluted sources causing diseases. All food and drink was stored in barrels known as “hogsheads”.

The passenger William Mullins brought 126 pairs of shoes and 13 pairs of boots in his luggage. Other items included oiled leather and canvas suits, stuff gowns and leather and stuff breeches, shirts, jerkins, doublets, neck cloths, hats and caps, hose, stockings, belts, piece goods, and haberdasheries’. At his death, his estate consisted of extensive footwear and other items of clothing, and made his daughter Priscilla and her husband John Alden quite prosperous.

No cattle or beasts of draft or burden were brought on the journey, but there were pigs, goats, and poultry. Some passengers brought family pets such as cats and birds. Peter Browne took his large bitch mastiff, and John Goodman brought along his spaniel.

Mayflower officers, crew, and others

According to author Charles Banks, the officers and crew of the Mayflower consisted of a captain, four mates, four quartermasters, surgeon, carpenter, cooper, cooks, boatswains, gunners, and about 36 men before the mast, making a total of about 50. The entire crew stayed with the Mayflower in Plymouth through the winter of 1620–1621, and about half of them died during that time. The remaining crewmen returned to England on the Mayflower, which sailed for London on April 5, 1621.

Banks states that the crew totaled 36 men before the mast and 14 officers, making a total of 50. Nathaniel Philbrick estimates between 20 and 30 sailors in her crew whose names are unknown. Nick Bunker states that Mayflower had a crew of at least 17 and possibly as many as 30. Caleb Johnson states that the ship carried a crew of about 30 men, but the exact number is unknown.

Captain: Christopher Jones.

Christopher Jones

About age 50, of Harwich, a seaport in Essex, England, which was also the port of his ship Mayflower. He and his ship were veterans of the European cargo business, often carrying wine to England, but neither had ever crossed the Atlantic. By June 1620, he and the Mayflower had been hired for the Pilgrims voyage by their business agents in London, Thomas Weston of the Merchant Adventurers and Robert Cushman. Few of the guests gathered for the wedding at St Nicholas Church, Harwich on December 23rd 1593 would have had any inkling that the bridegroom was to become a figure of international and historical importance.

The young mariner was Christopher Jones and his bride to be Sara Twitt, the 17 year old daughter of his neighbor across the street. By the time of his wedding, Jones’ father, also Christopher had already died and had left his son his share in the ship Mary Fortune. Thomas Twitt also bequeathed his daughter, Sarah, £20 and a twelfth share in the ship Apollo at his death. Christopher Jones jnr therefore was well placed to develop a sea-going career and commitments as a citizen of Harwich.

St Nicholas Church

In 1601 he was elected freeman of the Borough of Harwich and records show him acting as an assessor for tax and jury member. A son was born to the Jones within a year of the wedding, however, sadly, the infant died on April 17th 1596 and they had no further children. Sara herself died, aged 27, and was buried at Harwich on May 23rd 1603.

Christopher was married again within a few months to Josian Gray, herself a widow with seafaring connections. The marriage produced eight children and the couple moved to Rotherhithe in 1611. Jones’ career flourished further during this marriage and he was engaged in trading between England and Europe as well as shipbuilding.

The burial of Christopher Jones is recorded in the Parish Register of St Mary’s, Rotherhithe on March 15th 1622.

Masters Mate: John Clark (Clarke), Pilot. By age 45 in 1620; Clark already had greater adventures than most other mariners of that dangerous era. His piloting career began in England about 1609. In early 1611, he was pilot of a 300-ton ship on his first New World voyage, with a three-ship convoy sailing from London to the new settlement of Jamestown in Virginia. Two other ships were in that convoy and the three ships brought 300 new settlers to Jamestown, going first to the Caribbean islands of Dominica and Nevis. While in Jamestown, Clark piloted ships in the area carrying various stores. During that time, he was taken prisoner in a confrontation with the Spanish; he was taken to Havana and held for two years, then transferred to Spain where he was in custody for five years. In 1616, he was finally freed in a prisoner exchange with England. In 1618, he was back in Jamestown as pilot of the ship Falcon. Shortly after his return to England, he was hired as pilot for the Mayflower in 1620.

Masters Mate: Robert Coppin, Pilot. Coppin had prior New World experience; he previously hunted whales in Newfoundland and sailed the coast of New England. He was an early investor in the Virginia Company, being named in the Second Virginia Charter of 1609. He was possibly from Harwich in Essex, the hometown of Captain Jones.

Masters Mate: Andrew Williamson

Masters Mate: John Parker.

Surgeon: Doctor Giles Heale. The surgeon on board the Mayflower was never mentioned by Bradford, but his identity was well established. He was essential in providing comfort to all who died or were made ill that first winter. He was a young man from Drury Lane in the parish of St. Giles in the Field, London who had completed his apprenticeship with the Barber-Surgeons in the previous year. On February 21, 1621, he was a witness to the death-bed will of William Mullins. He survived the first winter and returned to London on the Mayflower in April 1621, where he began his medical practice and worked as a surgeon until his death in 1653.

Cooper: John Alden. Alden was a 21-year-old from Harwich in Essex and a distant relative of Captain Jones. He hired on apparently while the Mayflower was anchored at Southampton Waters. He was responsible for maintaining the ship’s barrels, known as hogsheads, which were critical to the passengers’ survival and held the only source of food and drink while at sea; tending them was a job which required a crew member’s attention. Bradford noted that Alden was “left to his own liking to go or stay” in Plymouth rather than return with the ship to England. He decided to remain.

Quartermaster: (names unknown), 4 men. These men were in charge of maintaining the ship’s cargo hold, as well as the crew’s hours for standing watch. Some of the “before the mast” crewmen may also have been in this section. These quartermasters were also responsible for fishing and maintaining all fishing supplies and harpoons. The names of the quartermasters are unknown, but it is known that three of the four men died the first winter.

Cook: (name unknown). He was responsible for preparing the crew’s meals and maintaining all food supplies and the cook room, which was typically located in the ship’s forecastle (front end). The unnamed cook died the first winter.

Master Gunner: (name unknown). He was in charge of the ship’s guns, ammunition, and powder. Some of those “before the mast” were likely in his charge. He is recorded as going on an exploration on December 6, 1620, and was “sick unto death and so remained all that day, and the next night”. He died later that winter.

Boatswain: (name unknown). He was the person in charge of the ship’s rigging and sails, the anchors, and the ship’s longboat. The majority of the crew members “before the mast” were most likely under his supervision, working the sails and rigging. The operation of the ship’s shallop was also probably under his control, a light open boat with oars or sails .William Bradford made this comment about the boatswain: “the boatswain… was a proud young man, who would often curse and scoff at the passengers, but when he grew weak they had compassion on him and helped him.” But despite such assistance, the unnamed boatswain died the first winter.

Carpenter: (name unknown). He was responsible for making sure that the hull was well-caulked and the masts were in good order. He was the person responsible for maintaining all areas of the ship in good condition and being a general repairman. He also maintained the tools and all necessary items to perform his carpentry tasks. His name is unknown, but his tasks were quite important to the safety and seaworthiness of the ship.

Swabber: (various crewmen). This was the lowliest position on the ship, responsible for cleaning (swabbing) the decks. The swabber usually had an assistant who was responsible for cleaning the ship’s beakhead (extreme front end), which was also the crew’s toilet.

Known Mayflower seamen

John Allerton: A Mayflower seaman who was hired by the company as labor to help in the Colony during the first year, then to return to Leiden to help other church members seeking to travel to America. He signed the Mayflower Compact. He was a seaman on ship’s shallop with Thomas English on exploration of December 6, 1620, and died sometime before the Mayflower returned to England in April 1621.

____ Ely: A Mayflower seaman who was contracted to stay for a year, which he did. He returned to England with fellow crewman William Trevor on the Fortune in December 1621. Genealogist Dr. Jeremy Bangs believes that his name was either John or Christopher Ely (or Ellis), both of whom are documented in Leiden, Holland.

Thomas English: A Mayflower seaman who was hired to be the master of the shallop (see Boatswain) and to be part of the company. He signed the Mayflower Compact. He was a seaman on the ship’s shallop with John Allerton on exploration of December 6, 1620, and died sometime before the departure of the Mayflower for England in April 1621. He appeared in Leiden records as “Thomas England”.

William Trevore (Trevor): A Mayflower seaman who was hired to remain in Plymouth for one year. One reason for his hiring was his prior New World experience. He was one of those seamen to crew the shallop used in coastal trading. He returned to England with _____ Ely and others on the Fortune in December 1621. In 1623, Robert Cushman noted that Trevor reported to the Adventurers about what he saw in the New World. He did at some time return as master of a ship and was recorded living in Massachusetts Bay Colony in April 1650.

Unidentified passenger

“Master” Leaver: Another passenger not mentioned by Bradford is a person called “Master” Leaver. He was named in Mourt’s Relation, London 1622, under a date of January 12, 1621 as a leader of an expedition to rescue Pilgrims lost in the forest for several days while searching for housing-roof thatch. It is unknown in what capacity he came to the Mayflower and his given name is unknown. The title of “Master” indicates that he was a person of some authority and prominence in the company. He may have been a principal officer of the Mayflower. No more is known of him; he may have returned to England on the Mayflower’s April 1621 voyage or died of the illnesses that affected so many that first winter.

The Mayflower was broken up and documents from 1624 record that Christopher Jones owned a quarter share of the boat. Whereas the Mayflower had, in 1609, been valued at £800, when it landed up in the breaker’s yard.

1620-2020

Acknowledgements: The Harwich Society, Wikipedia.