Parkeston

The site of Parkeston Quay and the village was partially on an island called “Ray Island” and partially on mud flats of the River Stour. Ray Island was not actually an island all the time, only at high tide. At low tide it was joined to the mainland by a stretch of marshland.

The site of the present village was originally called “Le Rey” a name given during the Saxon period. In the early nineteenth century Lewis Peake Garland had a dyke system constructed around the area of “Le Rey” or “The Ray” as it has become known.

In the Beginning.

Back in time people journeying to Holland travelled to Harwich along horrible bumpy roads in horse-drawn coaches doing their best to hang on to their luggage and their stomach contents before boarding the ‘packet’ boat to the Hook . If they were lucky they might get a bit of a breather at the Hotel on the Quayside before embarking on another couple of days self-inflicted torture on the North Sea. For years this was the way of things until half way through the 19th century The Great Eastern Railway Company pushed a line through to Harwich.

With the coming of the railway, business at the port took off. Looking to the future, the Company began making expansion plans .Unfortunately for them the good people of Harwich had other ideas. They liked things more or less as they were and didn’t fancy the idea of having a new quay and massive warehouses and shunting yards on their doorstep. They put up some fairly stiff resistance. Finally the local council gave the company the go-ahead but made it clear they would be taxed to the hilt for the Privilege.

This put the railway company in something of a bind. If they didn’t expand they would lose the chance of making bigger profits, and if they did they’d end up seeing most of the extra proceeds eaten away by a draconian local tax regime. But there was another, somewhat bolder, option. A couple of kilometres up the River Stour stood Ray Island, and soon a very ambitious plan was put together to develop the site and move the company’s business there lock stock and barrel. The site had everything the Company was looking for and, best of all, it was relatively cheap.

Ray Island had stood there more or less minding its own business for hundreds of years. It had changed owners and its name a few times but otherwise had been left largely alone. There doesn’t seem to be any convincing evidence that it was ever inhabited, except by flocks of sheep, before a successful attempt was made to reclaim some of the surrounding marsh, with the help of Dutch engineers. This produced some farm land in the early 1800s. Before this Ray island would have been surrounded by water at high tide and by the estuary mud and marsh at low tide. The water came in by way of what is now Bathside Bay and flowed round the Island re-joining the main river where the oil refinery stands now. The coast reached as far as Ramsey and what is now the Dock River was a tidal creek reaching as far as Little Oakley. It was deep enough to allow barges to reach Ramsey without too much difficulty .But all this was put paid to by the sea defences and the first railway line which was laid across the marsh around 1850.

This was the plan. Three embankments were to built, one to carry a road to the island over the original railway line and the Dock River then across the marsh, and one at each end of the island to carry a new railway line from London and on to Dovercourt Bay and Harwich.

When this work was completed more land would be Reclaimed and later turned over to farming. Piles were to be driven in close to the deep water channel for a distance of a about a kilometer and the marshland up to that point filled with earth taken from the High Hill and with huge amounts of imported cinders. This was the site of the new quay. At the same time Plans were also put forward to develop small village to house the construction workers and later the company’s work-force.

The project was given the green light by the give government and local council in 1874.The new quay was opened for business in 1883. It retained the name of Harwich but was called ‘Stour Quay’. That was later changed to Harwich (Parkeston) Quay, named after Charles H. Parkes, Chairman of the G.E.R. to the bewilderment of generations of British and foreign Travelers thereafter. The first workers’ houses were built at the same time as the quay.

There were also three somewhat posher dwellings for the Station Master, the Port Manager and the Marine Superintendent. This initial phase was quickly followed by the near completion of the village as it stands today. Although a few houses were for private renting the company owned the majority, and in some cases whole streets. Only railway workers could rent company houses and in many cases, when a certain scarce trade or skill was in demand, these tradesmen had to live in tied accommodation .The company was anxious to Have the greatest possible control over their workers who, in many cases, had to commit themselves on a ‘lose your job – lose your home’ basis.

The last streets to go up we’re Una Road, Foster Road and Edward Street. They were intended to be a cut above the rest and I dare say some of the people who lived there thought themselves as being a cut above those ‘up the other end, of Parkeston. After the opening of the quay the population of the village grew rapidly.

Churches and Mission Halls.

Wesleyan Methodist Church

The First church in Parkeston was the Wesleyan Methodist Church situated in Garland Road and built in 1887 at a cost of £900.00 and designed to hold 200 people. Prior to this, Religious services had been held in a small wooden at the back of Princess Street. There are several foundation stones laid and some interesting bricks which have initials on them. It was a trend at the time that local people were Invited to make contributions to the building fund, in exchange for a brick with their initials on.

St.Gabriels

With the village of Parkeston expanding fast, the parishioners decided it was time they had their own church, “The Tin Tabernacle” opened its doors on the 13th June 1887. The picture shows their iron church and the vestry made of a disused railway carriage. A new organ was purchased with donations from three anonymous directors in memory of the crew of the “Berlin” who had lost their lives in the 1907 disaster. The church was demolished in 1973 to make way for the current railway club.

St. Paul’s

St Paul’s

St. Paul’s Church was the largest church in Parkeston, built in 1914 between Makins Road and the Main Road on Land granted to the church by the Great Eastern Railway Board in 1909. It was dedicated to St. Paul and had provision for a congregation of 350 people. The outstanding highlight of the church’s history was the erection of the lych-gate after the 1914-18 War as a memorial to the men of Parkeston, who had given their lives for their country.

Lord Claud Hamilton

The proceedings commenced with a luncheon, at which the chair was taken by Lord Claud Hamilton, supported by many other important gentlemen. After lunch the company proceeded to the church where, the bishops, clergy and choir having robed, a procession was formed, making its way to the site of the new church in Makins road. A large crowd had assembled round the site, and many of the residents along the line of the route had displayed flags and bunting.

Memorial Organ

A Beautiful Organ, the gift of three shareholders of the Great Eastern Railway Company in memory of those who lost their lives in the ss Berlin disaster, has been presented to Parkeston Church in place of an old American organ. The new instrument is a one-manual with six stops, and one octave of pedal pipes. A brass plate bears the inscription: “To the Glory of God and in memory of those who lost their lives in the wreck of the ss Berlin, G.E.R. Feb. 21, 1907 .This organ is given to Parkeston Church.” The dedication took place on Monday evening. Special prayers were said by the Rev. E. C.H. Pyemont, and an address was delivered by the Vicar of Harwich, the Rev. J. A. Telford, formerly priest in charge at Parkeston. At the conclusion of the service Mr. G. Mott, B.A., gave an organ recital. The organ was originally installed in St. Gabriel’s Church, but later moved to the new Church, St. Paul’s, which was built especially for the Railway Staff in 1914. The organ builder was Frederick Halliday from Highbury, London. It was later rebuilt by Rest Cartwright at an unknown date.

In 1967 Bishop and Son restored the instrument and painted the classic case white with gold front pipes. St. Paul’s Church closed in 2014 and has now been sold. All the contents have to be removed without further delay, or risk being lost. Negotiations are in hand to try and save this historic instrument, which is part of the history of Essex and of the Great Eastern Railway.

Last Service.

A Large congregation gathered at St Paul’s on Sunday 26th January 2014 to take part in the emotional last service to be held there.

When I in awesome wonder

Consider all the worlds

Thy hands have made

I see the stars

I hear the rolling thunder

Thy power throughout

The universe displayed

My Savior, God, to Thee

How great thou art

How great thou art

My Savior, God, to Thee

How great Thou art

Sent Him to die,

I scarce can take it in;

That on the cross, my burden

gladly bearing He bled and died

to take away my sin

My Savior, God, to Thee

How great thou art

How great thou art

Then sings my soul

My Savior, God, to Thee

How great Thou art

How great Thou art

Village Life

Parkeston post office

In 1897 the Co-op opened a branch comprising butchers, a grocery and a drapery. Arguably the most significant contribution the Co-op made to village life was the provision of a meeting room which doubled as a library for a while. Not that the Co-op was the only shop in Parkeston, far from it. Although the more senior villagers argue about exact numbers, even in the early years of the last century the number stood at least twenty two. Bakers’ Green Grocers was at the east end of the village and was run by the family. The entrance was on the corner of Princess Street. Alan Bloomfield’s Sweets and General store was in Garland Road just before the pub. Enid Hazelton’s Hairdressers was on the right hand side of Hamilton Street.

Mick Good’s General Store and Bakery next door was a wooden building, Bread, rolls and cakes were made on the premises for the village, trains, ships and hotel.

Mrs Brown’s General Shop and Green Grocery was on the corner of Garland Street and Tyler Street. Sweets etc. in the Garland Road shop and greengrocery in the Tyler Street shop. A mirror between the two rooms made it possible to keep an eye on one room while serving in the other.

Mrs Silver’s Sweet Shop was half way up Tyler Street on the right hand side.

The Cabin in Garland Street was once a bicycle shop and repairers, a builder’s DIY shop run by Mr Barker, a shipping agents and general store.

Block Durrants General Store named after the owner had an automatic cigarette machine which stood outside on the pavement.

Mr Tom Went’s Shop in Garland Road sold newspapers flowers and greengrocery which was grown on a small holding and which is now the Welfare Park.

On the corner of Adelaide Street once stood the CO-OP. The yard was used as a milk store, paraffin store and Stables where the horses were kept for coal carts.

Spindlers’ General Store was on the corner of Una Road.

Len Dacy’s Barber Shop, a brick and wood, two storey building, stood on the main road opposite the Garland Road entrance. The lower part being the shop.

Above the Barber’s shop was Kingsbury’s Workshop who did repairs for the local house holders.

The social life of the village was well catered for. There were meeting halls at the Co-op, the Chapel and the Tin Tabernacle, and later the Railway Club and the Scout hut in Foster Road. There was a sports field on Hamilton Park for football, cricket, bowls and quoits.

Social Club

The Railway Club was originally part of the British Railways Staff Association (BRSA) group of clubs whose members were exclusively British Railway employees. The club was opened in February 1918 as the “British and Foreign sailors rest” by Commodore Tyrwhitt. Parkeston Railway Club bought it from the Admiralty after the war, however, following de-nationalisation of British Rail and the sale of Sealink the club was sold to its members. So although the name “Railway Club” has been maintained it now has no connection with any rail company and is a private members club.

Although the clubs history goes back many years the present club was opened in 1975. It has one large bar with a pool table in an annexe. There is also a large function hall and kitchen for use for weddings, birthdays and anniversary parties etc. as well as being used for indoor bowls.

Although the Railway was without doubt the principle employer not everyone who lived in the village worked there. A clothing factory was set up on the corner of Foster Road which employed mainly women. The building was taken over by the Navy at the outbreak of the Great War and was later handed over to HM Customs. The brickfield at the end of Una Road was in operation up to the start of the Second World War but remained a unique example of industrial architecture of its type.

So who then were the first Parkeston villagers? Many of the unskilled dock labourers would undoubtedly have been ex-farm workers from the nearby countryside, Some of whom would have been recruited earlier to work on the construction of the quay And who simply stayed on. Trade at Parkeston grew faster than it took to train local labour so it seems inevitable That there would have been a degree of touting for special skills at other ports. The railway needed engine drivers, firemen, guards, signalmen, shunters and lenghtmen, Railway managers, booking clerks and platform workers. The operation of the quay Call for crane drivers and dock workers to handle cargo and to ‘coal up’ the ships.

There is also evidence that the quay shipped live animals to the continent which would Have called for skilled stockmen. Add to these trades like boilermakers, shipwrights, carpenters And marine engineers and one can begin to appreciate the recruitment problem that faced the Company in those early days, a problem made worse by the fact that in a relatively Low population area like Harwich and Dovercourt local workers were neither skilled nor plentiful. And so Ray Island, a lump of land at the edge of the River Stour, was transformed, practically overnight, into the village of Parkeston, an almost self-sufficient, thriving community, populated by people from far and near. This, of course would have included the first children of Parkeston who would have brought with them a host of different games from a number of Places across the British Isles.

Schooling

On the 4th October 1888, the Ramsey Board of Schools opened a school in Parkeston. It was opened a Board School and as this was three years before the Government passed the 1891 “Free Education Act” fees were charged to pupils. Juniors and Infants paid 2d. a week but the eldest children in any family paid 4d. a week.

The school had accommodation for 100 boys and 100 girls as well as 178 infants; it was divided into two sections buy a high brick wall separating the boys section from the girls. The headmaster in charge of the school was Mr W.Hudson who taught the boys and a Headmistress, Miss E.Meyrick, who had charge of the girls.

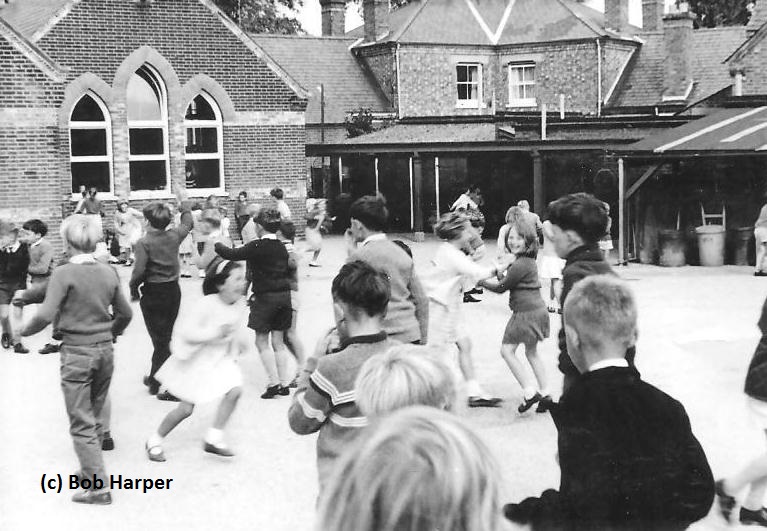

Parkeston School

Parkeston School was built by the Ramsey School Board and opened on the 4th October 1888 at the top of Hamilton Road at a cost of £2,190. Parents had to pay until 1891 so attendance in the first couple of years would have been patchy. The capacity was 200 plus 178 infants. The school was divided into three separate units, mixed infants, boys elementary and girls elementary. The first day of opening admitted 42 boys and 41 girls.

Education at its Best

From Foster Road it was easy to walk to school. We didn’t have a “Lollipop Lady” as there wasn’t much heavy traffic in those days. Car Transporters and Container Lorries were a thing of the future.

It had seemed a wrench to leave our Mums standing at the school gates. We didn’t attend a play school or crèche in those days, so we were not prepared for what lay ahead.

If I remember correctly our first teacher in the infants was Miss Thurlow. I don’t know whether she was a “Miss or a “Mrs.”, but like all teachers she was “Miss” to us.

We soon settled in our class room and got on with our lessons. It didn’t seem very long before we heard the rattle of metal crates containing small bottles of milk. These were issued by the milk monitor and we quickly drank them and out to play we went with strict instructions to go to the toilet. When I think back, what an experience that was. No friendly roll of toilet paper hanging there. This was issued by “Miss”, who would ask “How many pieces?” It was hard luck if you hadn’t request sufficient. It was worse if you had gone for a ‘quick visit’ and a more important movement took place. You had to shout out to someone to fetch some and patiently wait. As the toilets were outside in the playground everybody knew of your problem. Naturally there were no locks on the doors and some of the mischievous boys would run through the girl’s toilets and push the door open.

During the first term, before lessons commenced in the afternoon session, we all had to lay down on little canvas beds. We were supposed to sleep, but I don’t think anybody did. at least we were resting and if you got caught opening your eyes you were reprimanded.

We were soon taught to chant our “Arithmetic Tables”. Commencing with “Two twos are four”, we would shout at the top of our voices. But as we progressed and the “Tables” appeared more difficult, we didn’t make quite so much noise. The Headmaster, Mr Charles Uphill, would come and listen to our chanting and would fire questions at us. So you ensured you always knew the answer on his next visit, as he always remembered the culprits. If today’s small calculators had been invented then I don’t think he would have allowed them in school.

Many splendid entertaining productions were performed at Parkeston School. The West End theatres of today would never have competed with us. I remember being a fairy in “Cinderella”. I don’t know why I was chosen as I was very tall for my age and rather awkward. But I felt important. My mum had made my dress out of crepe paper, and my wand was covered with silver paper carefully collected from our rationed chocolate. My favourite role was in “Who killed Cock Robin”. I can remember my words still.

We were encouraged in many sporting activities. These usually took place in the playground or on Hamilton Park. Sports Day was one of the highlights of our sporting calendar. There was a large wooden and corrugated iron grandstand on Hamilton Park where all the spectators gathered to watch and cheer. It was mostly parents and relations, which consisted of the villagers. We felt so important, in our minds it was just like the Olympics. In the early days I was restricted to the “Three-Legged Race” as I couldn’t run very fast. I usually fell over before completing the race, pulling my partner over with me. I also dropped the egg in the “Egg and Spoon Race” Later on, the school obtained some high-jump equipment which was quite popular. I did eventually excel at the high-jump and won the inter-schools competition held on the Barrack Field at Dovercourt, and was presented with a silver cup.

In the summer time we were taken once a week by coach to the open air swimming pool at Dovercourt, were we were taught to swim. No matter how cold it was we couldn’t miss the trip. The coach ride itself was something to look forward to, as we were used to walking everywhere as not many families in the village owned a car. the school was heated by a hot water pipe and radiator system served by a coke fired boiler. This was operated by Mr Arthur Pratchett, the school caretaker. He was amazing, he knew every child’s name and he would shout at us if he caught us playing near the coke. We would instantly obey his voice of authority as we had every respect for him. He was proud of “his” school and made sure we behaved ourselves when he was about.

In the winter time the hot water pipes fixed to the skirting boards were a great attraction to sit on. We would jump up with warmed bottoms and then put our cold feet on them.

There was no school uniform in those days as clothing was still rationed. Our mothers did the best with what was available. I know that the same clothes went to school every term, but on different children. I remember being so proud of my New skirt that my mum had made me. It was black, with rows of pretty bias-binding around the hem. I wasn’t aware then, but the black-out curtains from the war had been used up. If I wore out the elbows of my hand knitted cardigan it would be un-pulled and re-knitted with some more wool added. Or, it would become gloves, socks or a scarf. Our mums were marvelous how they overcame the difficulties of rationing and shortages. We didn’t seem to come to any harm, and thrived.

As we reached the age of ten we were prepared for the “Eleven Plus” examinations. A preliminary test was held in the dining room which didn’t seem too bad in the safety of our own little school and with our own nice teachers. When the dreaded day came to go to the “High School” and sit the examination with all the children for the surrounding schools it was quire frightening. Parkeston School had a good reputation for its pupils progressing to the High School, but I wasn’t one of them. I was destined for the Hill Secondary Modern School.

Although we lacked certain material equipment after the war we benefited from a good quality of basic sensible teaching methods and were encouraged to progress to the best of our ability. Parkeston School was a happy school where we not only learnt the three “Rs” but common-sense, respect for authority, and how to enjoy ourselves. The saying “School days are the happiest days of your life” is quite true regarding Parkeston School.

Reprinted from Parkeston Society Villager by Ann Raymond.

Streets.

Most of the terraced housing in Parkeston was built for railway employees and some of the streets in the village have names that can be theoretically linked to the shipping and general activities of the railway,Parkeston is made up of eleven streets, eight of which were constructed after 1883 when the quay first opened.

Adelaide Street

Adelaide Street developed in the mid-1880s on much the same lines as other Parkeston streets – rows of well-built terraced houses, where close knit relationships developed, and back doors were always open. One can imagine the communal grief which occurred when tragedy struck, such as the devastating loss of life with the sinking of the “Berlin”. Adelaide Street was named after. The “Adelaide” a paddle steamer built in 1880.

Coller Road

Named after one of the directors of the Great Eastern Railway of that day. It may have been Constructed as another exit from the village, additional to garland road and via Hamilton Street.

Edward Street

The last of the Parkeston streets to be developed, the first house was erected in the early 1930’s, The outbreak of war in 1939 halted development and did not resume until after 1945. The street takes its name from Local builder and Mayor Edward Saunders, who owned the brickworks in Una Road. All the earlier properties are constructed with bricks produced In the local brickworks before its closure.

Foster Road

Running parallel with Una road was developed during the early 1900’s. It derives its name from the corset manufacturing company at the eastern end of the road, Operated by the Foster Manufacturing Company. In later years the premises was used by H.M.Customs and Excise and served as the local customs house.

Garland Road

Named after the local squire and landowner, Squire Edgar Walter Garland who resided at Michaelstowe Hall. Many would say that at this time it was the main street and the hub of retail activity. In this view the children pose for the photographer outside the shop of C H King butcher/grocer) with Dowdy the chemist opposite, although the road was one of the first in the village to be developed, development was originally confined to the northern side only.

No buildings existed on the southern side until 1897 and several of the existing properties on this side of the road date back to 1897 and 1898.

Hamilton Street

Hamilton Street

(c) Rik Alewijnse

The name of this road may have been named after “Lord Claud Hamilton”, a director of the Great Eastern Railway at the time of development of Parkeston. He is believed to have been a regular visitor to the village. It could also have been named after the Great Eastern Railway vessel P.S Claud Hamilton which in turn was named after Claude Hamilton. The ship was built in 1875 and entered service in the same year from Harwich to the continent.

The street was developed during the 1880’s but housing was restricted to the southern half, the northern half providing sites for the local primary school, the church and the village hall.

Makins Road

Named after one of the directors of the Great Eastern Railway of the same name and may have been the beginning of proposed new development which was not proceeded with.

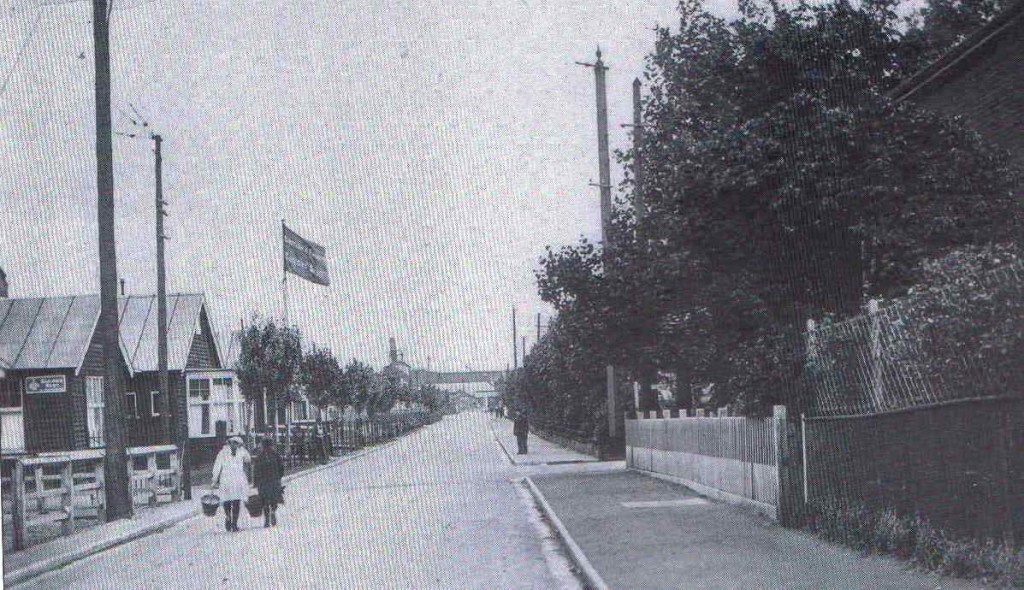

Parkeston Road

The view down to Parkeston Quay after the First World War. On the right is the junction with Coller Road and one of the houses here was that of the stationmaster, Mr Tyzack. On the left hand side, the first of the wooden buildings has a board announcing ‘Sailors Rest’ and the flag flying was that of the British and Foreign Sailor’s Society. The old Parkeston Railway Club occupied a collection of wooden buildings opposite the playing fields and can be seen here.

Included in the Railway Club was a dance hall, committee room, games room, tea room, sweet shop, billiard room and public baths.

Princess Street

Named after the paddle steamer P.S. “Princess of Wales” which was a two masted paddle steamer which operated between Harwich and Rotterdam and from Parkeston Quay to the Hook of Holland; her maiden voyage was on the 6th July 1878. After a career of 18 years she was sold for scrap on the 16th May 1895. The street was developed early in the history of the village with Properties on each side of the street.

Tyler Street

The growth of Parkeston was based upon the development of Parkeston Quay when the Great Eastern Railway Company decided to move its main passenger service from Harwich to a vast expanse of land which allowed many opportunities for expansion. The venture was completed and opened on February 15th 1883 by Charles Parkes, GER Chairman. By 1901 the census showed that over 60% of the villagers were employed by the railway.

Tyler Street was typical of the development, terraced houses built between 1883 and 1885. The Lady Tyler was a paddle steamer operating out of Parkeston Quay. The building in the bottom left is the Wesleyan Chapel Sunday School entrance.

Una Road

Una Road (c) Rik Alewijnse

The first road to be developed on the west side of the A604. Named after the vicar of the parish of Ramsey’s daughter “Una Wood”. The development of the road took place in two stages, The earlier development extended from the main road as far as the site of the old brick works. Housing development continued on each side of the road, many houses being constructed of locally made bricks. The final stage of development was not resumed until after the end of the war.

Last flight of The Lucy Quipment

Lucy Quipment

17 July 1944 saw the 493rd BG attacking targets to support the Invasion. Over Coulanges railway bridge, flak crippled two of Lucy Quipment’s engines and shrapnel peppered her fuel tanks. She really had some loose equipment and pilot, Lieutenant Robert L. Millhollin realized that their chances of reaching Debach were slim but none of the crew were hurt and fuel, vapouring from holed tanks, had not ignited: Lucy had served them well, they wanted to take her home.

Lucy Quipment had limped home, her crew were safe. Wearily, the old bomber settled seawards but did not quite make it. Had she crashed in Harwich or Parkeston, the results would have been devastating but fate guided her final flight towards a piece of wasteland separated from the Stour by the railway embankment. Slithering into a large shallow pool, Lucy left her tail near the point of impact, bounced, then disintegrated in a 500 yard trail of fragments. Total destruction was assisted by anti- tank blocks, Lucy shattered one of them, spreading her remains for some distance beyond. Countless pieces of Liberator lay everywhere.

Crash Site

In later years, Carless Chemicals built a refinery on part of the site, reclaimed from the marshland. No doubt, remnants of Lucy lie beneath their storage tanks. Plans for further building prompted action and a small team gathered on site in August 1976. Short on sanity but saturated with enthusiasm, our first task was to winch ashore the abandoned wing section. lan Hawkins bravely waded through the foul-smelling water to attach the winch cable.

Gradually, the ‘island’ of wreckage eased landwards including a complete main undercarriage leg and tire, still retracted in its housing. ‘It was sad to watch old Lucy, our Lib, fade away into the clouds, particularly when I saw, for the last time, my wife’s nickname, “Ruskin” painted on my tail turret.

Crew

While others dismantled this, I paddled about searching for smaller items. Wearing waders, I found most of the pool accessible and soon grew accustomed to the stench. Clinging mud hindered movement but I found a partially burnt fuel tank which I emptied and adapted to float pieces ashore. Others concocted their own methods and soon we had a worthwhile selection of artefacts to tell the tale of Lucy Quipment. A major problem was getting larger pieces across the lagoon but we discovered a crude causeway just below the surface. Using a piece of wing as a sledge, we became our own dog team.

The secret lay in gaining momentum on firm footing before you hit the sludge. Miss the causeway and you received a very unhealthy baptism and the smell lingered for days, as two of the team discovered.

Items recovered from an aircraft can pay tribute to its crew and excavations are happier in the knowledge that they survived.

(c) Ian McLachlan, Final Flights – Dramatic wartime incidents revealed by aviation archaeology.

Childs Play

A Short History of Parkeston and some Personal Recollections.

Kids just aren’t the same as they were in my day”. You hear it all the time, and you may have said it once or twice yourself. “They’re surly and rude, and they’ve got no respect for their elders. They’re stuck in doors in front of the telly or up in their rooms playing mindless computer games. That’s if they’re not blasting the neighbours with their stereos, out mugging old ladies or breaking into someone’s home. Why don’t they go out and play like we used to? They’re always complaining about being bored. We were never bored .they’ve got no sense of adventure.

I grew up in Parkeston in the 1950s in what, looking back, was a Largely care free and safe setting. There was always plenty of other children to play with, plenty Of places to go and things to do. As far as we were concerned the street, being almost empty of traffic, existed solely for the purpose of providing us with somewhere to mess about. The range Of games seemed almost endless, although not all were completely harmless, especially those played on dark nights. There were plenty of places to go that were out of sight of adults.

Hamilton Park

I have fond memories of Hamilton Park, where games of either football or cricket seemed to go on twenty four hours a day, And certainly well after it was too dark to see the ball. The brickfield was one large adventure playground complete with tunnels and assault courses; Parkeston woods, the High Hill, and the lakes that stretched from one end of Parkeston Quay right down to the end of where the oil refinery is now, and so on. During the daylight hours they were the focal point for children to meet up and play football or cricket or one of the many games that were in season at the time, be it five stones, Marbles, conkers or whatever. Edward Street was particularly handy for trolleys. Getting round the corner at the bottom was the big problem and didn’t always go according to plan. It was on dark nights that the streets came into their own, and when the greatest concentration of children gathered. There was no end to the variations on the ‘hide and seek’ theme and it was not Unusual to see, or hear, great hoards of kids charging about either looking for someone or trying To avoid being caught. .

The High Hill also had its attractions. The hill itself was there to be slid down; cardboard an tin in the summer and sledges in the snow, while at the top were a load of trenches left over from the war. During the war there was a firing range at the bottom of High Hill. If you dug into the bank a bit you could come up with handfuls of old bullets.

Parkeston Brickworks

The Brickfield at the end of Una Road was full of stuff to play with. The air tunnels to the kilns were just big enough for a boy to crawl though if you could summon up the courage. The whole area lent itself very well to playing of war games. There were plenty of bricks lying about that did for hand Grenades. They didn’t explode like the real thing but still managed to leave a lasting impression if you got hit by one. Now and again the battle might spill out into Una Road and a half a house might find its way into someone’s front room via half-house -brick-sized hole in the window. This was the signal to end hostilities as the only priority then was not to be the last one Seen vanishing up the road.

Further up the woods, where the oil refinery is now, was an area of land covered with low barbed-wire entanglements from the war. We were told not to go in there Because there were said to be mines that had not cleared. We searched and searched For one to play with but never managed it. What a swiz! If you carried on a bit you came to the wreckage of an American plane in the last Pond (The Liberator). Near there was a path that led over the railway line onto the Shore. You had to be careful not to be spotted. Once there you could get all the way to Wrabness if you were of a mind.

The most popular place for fishing was the Dock River. All you needed was a Bamboo pole, some line, a cork float (some posh kids bought real ones from the shop),a hook and some bait-then you were off. The best bait was those little red and white Striped worms you got from lifting clods of dried human waste from the sewerage works At the end of Garland Road. They stunk to high heaven but the eels liked them. Sometimes mullet used to swarm up the river. You stood no chance of catching them With a hook and line so we made spears with a bunch of sharpened bicycle spokes tied Round the end of a stick. These were chucked at the fish with an equal lack of success.

There was always something going on at the Welfare Park. Among the most vivid of Memories of the Welfare Park are of the fete that was held there each year. There were Loads of things to spend your cash on, if you had any. There was also a live skiffle group And a wrestling match and the crowning of the village queen.

Conclusion

It may well be the case that the number of children of secondary school age has continued to fall since 1982, and of those that remain most will have become ever more isolated from the real outside world by way of the further introduction of the dreaded computer game and the mobile phone. Perhaps I am being over pessimistic, but either way the tradition of play that had been so healthy for so long appears to be on its last gaps.

I speak to my friends a lot about our childhood. Half the time is taken up talking about how the youth of today are such a horrible lot, the other half by stories about the horrible things we got up to. Still the penny doesn’t drop.

Copyright. Douglas Tovell August 2000.

Parkeston Gallery

Click “Play” to start the gallery slide show.

We hope you will enjoy browsing these wonderful photographs.

We are adding more information to this site on a regular basis, if you wish to submit any photos or provide any information, please use the contact page at the bottom of the screen.

Acknowledgements:

Douglas Tovell. The Harwich Society. Final Flights – by aviation archaeology. Rik Alewijnse.